MFA Blog

The Lone Wulf: Meet the Father of Gestational Surrogacy

The 1986 Baby M case marked a major turning point in the history of surrogacy in the United States, not only because of the ethical quagmires it exposed but also it coincided with the beginning of (mostly) the end of traditional surrogacy in the United States. In 1985, a South African-born Cleveland- based gynecologist and reproductive biologist named Dr. Wulf Utian wrote a letter in the New England Journal of Medicine. In it, he stated that he had created a baby using a surrogate’s uterus, another woman’s egg and her husband’s sperm.

Sometimes, history is made when alphabetically you come last but you end up first.

The 1986 Baby M case marked a major turning point in the history of surrogacy in the United States, not only because of the ethical quagmires it exposed but also it coincided with the beginning of (mostly) the end of traditional surrogacy in the United States. In 1985, a South African-born Cleveland- based gynecologist and reproductive biologist named Dr. Wulf Utian wrote a letter in the New England Journal of Medicine. In it, he stated that he had created a baby using a surrogate’s uterus, another woman’s egg and her husband’s sperm.

Before he fell out with the Apartheid government back home, Dr. Utian had been doing most of his research in menopause, being the first to describe way back in 1967 that it was a health-related issue. (Dr. Utian told me that because he happened to work at the same hospital in Cape Town as Christiaan Barnard—the first doctor to do a human-to-human heart transplant—he benefitted from all the research money the hospital started receiving after that successful surgery).

When he arrived in Cleveland, Ohio in the mid-1970s, Dr. Utian helped to set up a fertility clinic at Mt. Sinai Hospital, which became one of the most successful fertility clinics running in an academic center in the country. “And out of the blue one day I got a phone call from a cardiologist from New Jersey,” he told me in a Zoom call from South Africa where he now spends part of his retirement. “And he said, ‘I will be honest with you, you are “U” in the alphabet so you are the fifth person I am calling.’” Everyone else had said no.

The cardiologist, Elliott Rudnitzky, told Dr. Utian that his wife had had a Caesarean hysterectomy and that their baby had died soon after. However, his wife still had functioning ovaries. The cardiologist said they had a good friend in Michigan—which turned out not to be the case—and she was willing to be their surrogate.

Turns out, Noel Keane (the Dearborn-based lawyer who had been the first person in the U.S. to write up a commercial surrogacy contract back in 1976) had actually found them a willing surrogate in Michigan. “It was sort of [the cardiologist’s] idea in a sense because even though people probably talked about this before, he was the one who [proposed it],” Dr. Utian said. The idea of implanting embryos from one womb to another had been done on animals for years. “So,” he said, “it was not a unique concept.”

Pieter van Keep, at the time Director-General of the International Health Foundation, with Dr. Wulf Utian

Dr. Utian told Dr.Rudnitzky that he was interested. But the hospital board at Mt. Sinai said before Dr. Utian could proceed, he needed to get the permission of the local religious leaders, as the hospital had seen protests over their assisted reproductive technology (ART) work. “The rabbi, to my surprise, told us ‘you know it’s written in the Torah be fruitful and multiply onto the land so therefore since you are helping people get pregnant, it’s kosher,’” Dr. Utian said, adding that while the Catholic bishop never got back him, years later the bishop’s secretary became one of his patients.

The hospital, of course, required psychological screenings on both the gestational carrier and the couple. They also wanted airtight contracts that considered things from whether the surrogate should take prenatal vitamins to if there was a fetal anomaly would the couple consider termination. “We actually fell out with Noel because we were very keen about certain rigid ethical issues,” Dr. Utian said. “And with all due respect, he skirted to the edge of a lot of that stuff.”

They knew that they wanted to use the surrogate’s natural cycle so, “we manipulated the cycle of the biological mother, coinciding cycles,” he explained to me. “And then we did the embryo transfer and so that was all I was responsible for. And then we followed the pregnancy and once we were happy with [how things were progressing] she could deliver wherever she wanted.”

The 7-lb 3-oz baby girl, who in the press was called Shira, was born in suburban Ann Arbor, Michigan in April 1986. “It was the first time in world history that a woman who gave birth to a baby was not the [biological] mother,” said Dr. Utian. Shira was also the world’s first baby where a judge ruled that her biological mother and not the surrogate should be listed on the birth certificate.

The birth—and the court ruling—were watersheds in changing how surrogacy worked. “There was a lot of excitement from people because suddenly you had this whole group of women out there who had uterine abnormalities or recurrent miscarriages or other reasons why they couldn’t carry a pregnancy but they still had eggs and ovaries,” Dr. Utian said. “So I mean, we were inundated with phone calls.”

After her birth, Mt. Sinai became the center for gestational surrogacy for a number of years. “We started getting patients from all over the world and I recorded a couple years later our pregnancy rate I think was around 25%, which was at that time was an outstanding,” he said. “I sort of stepped away from it later because it —developing the technology, the way to freeze the eggs and store them— became a recipe. And I like to think of myself more as a clock maker than a timekeeper.”

Dr. Utian said he is still in touch with the family (they send holidays cards each year) and even attended the girl’s bat mitzvah where her mother made a speech. “She called me up to stand next to her,” Dr. Utian told me, “and she was crying, everybody was crying and I had tears running down my face.” He was also invited to Shira’s wedding a few years ago but he and his wife were in South Africa so they could not attend. According to a 2016 CDC report, 95% of all surrogacies in the U.S. now are via gestational carriers.

—This story is kindly excerpted from Ginanne Brownell’s upcoming book “How I Became Your Mother: My Global Surrogacy Journey.”

Infertility’s Impact on the Latinx Community

Infertility is defined as the inability to conceive within one year of trying. For many women and couples, experiencing difficulty conceiving is navigating uncharted territory. Infertility impacts one in eight women, yet research shows that Black and Indigenous people of color experience infertility at even higher rates. The impact of infertility within the Latinx community has not been thoroughly researched, in part because of the assumption of high fertility rates among Latinos. As a result, the barriers that infertile Latinos face in their efforts to build families remain virtually invisible to their physicians, social scientists and policymakers.

The cost of infertility treatments has been identified as a major barrier to accessing treatment for many people suffering from infertility. The average IVF cycle can cost anywhere from $12,000 to $17,000 (not including medication) and with medication the cost can rise to around $25,000. Insurance coverage for IVF varies depending on the insurance company, state-specific legislation, the woman or couple’s age and reasons for infertility and even the insured’s relationship status. Latinx and African American households are at an even greater disadvantage when it comes to accessing treatment because their annual incomes are substantially lower than that of white and Asian households. Research suggests that African American and Latinx women are less likely to access assisted reproductive technologies (ART) like IVF treatments in part because of economic disparities.

Even in states with comprehensive insurance coverage for infertility services, the predominant group to access those services tend to be Caucasian, highly educated and wealthy. African American and Latinx women are underrepresented in terms of who is accessing treatment even though they are more likely to suffer from infertility. The reasons for disparities among Latinx women accessing infertility treatment are not yet clear, but researchers suggest that potential barriers may include lack of information and education, racial discrimination, lack of referrals from primary care physicians and inadequate insurance coverage. Some studies suggest that language and cultural barriers create obstacles in finding medical information, quality healthcare and treatment.

In Latinx communities, fertility issues are often not discussed, leading many Latinas struggling with infertility to experience feelings of shame, guilt, and isolation. Meanwhile anything having to do with sex and marriage is still perceived as somewhat taboo. Religious stigmas regarding fertility treatments within Christian and Catholic religions can create conflicts for individuals who are struggling to conceive. One study aimed to better understand the factors that impact patient experiences obtaining fertility care found that Latinx participants were twice as likely as white participants to report being very/extremely worried about using science and technology to conceive.

U.S. television personality Lilliana Vazquez, who struggled for years to get pregnant, shared her personal experience coming from a traditional Catholic family. "I was dealing with the fact that I might not be able to have children and I was talking about using science,” said Ms. Vazquez. "To my very Catholic family that's going to be like I'm trying to play God." Traditional religious views about the importance of reproduction, and the idea that pregnancy is God's (and not science's) gift to women, also underlie feelings of shame and guilt associated with infertility. Part of the stigma also likely stems from the perception that Latinx women are naturally very fertile, or hyperfertile, a stereotype rooted in racist ideas and with complex ties to colonization.

Adriana Alejandre, a licensed family and marriage therapist and the founder of Latinx Therapy, and Blanca Amaya, a licensed clinical social worker, shared their perspectives on infertility in their community in a live Q&A. “There are a lot of feelings of loss and depression and anxiety regarding [infertility] because women have this expectation that they will be able conceive,” says Ms. Amaya. “You’re grieving a life that you envisioned for yourself, but you don’t get to have that,” said Ms. Alejandre. “I have had clients who have needed to process how discriminatory, dry, and shameful even, [it was] when doctors told them [their diagnosis].” Ms. Alejandre explained how these conversations are often traumatic for women and can lead to hesitation around the medical field as a whole.

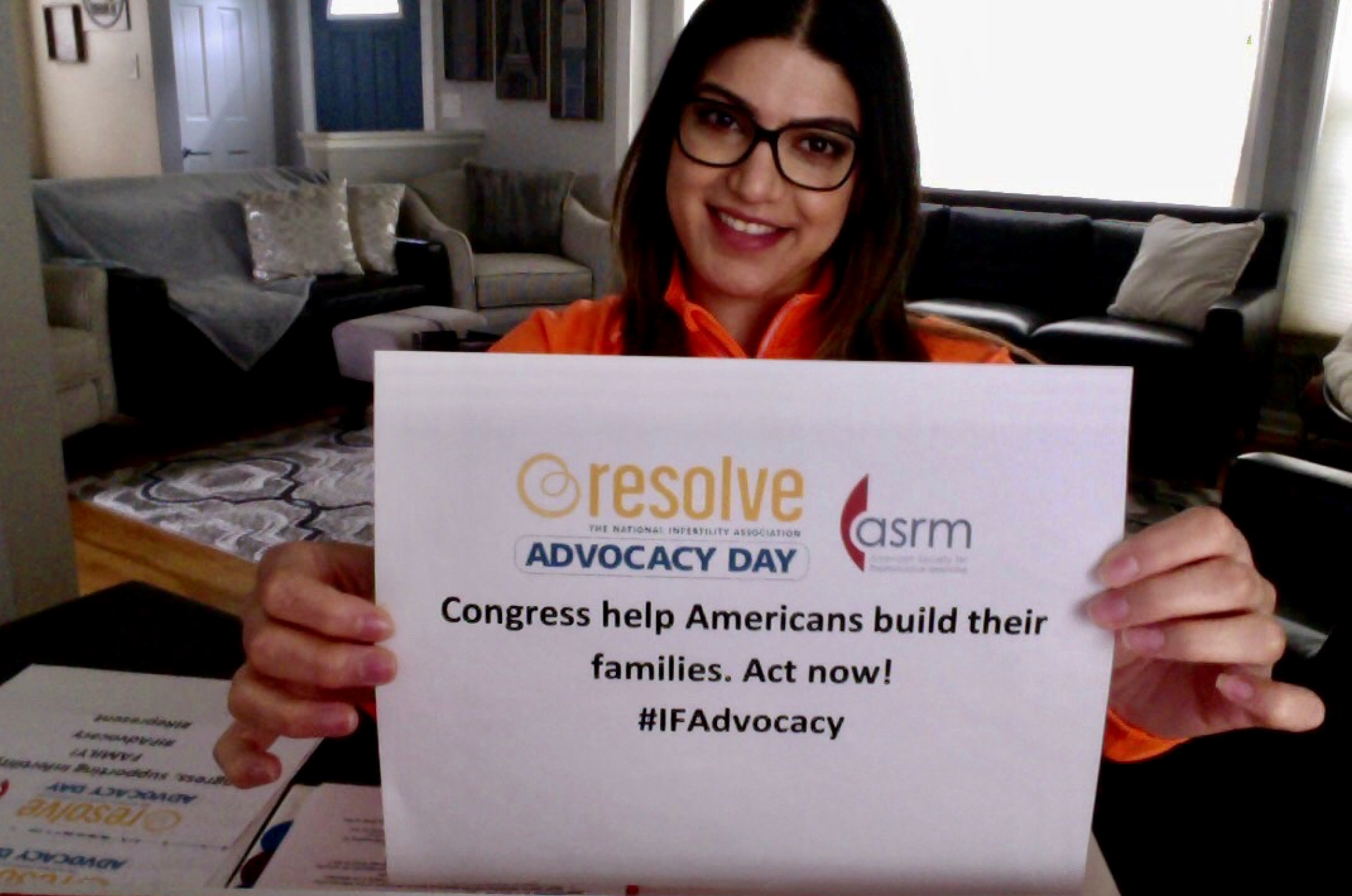

It is increasingly important to raise awareness about how infertility disproportionately impacts underrepresented communities and increase access to medical information and treatment. Infertility is an isolating experience for many therefore it is especially important to find a community of people who can provide support. If you or someone you know is experiencing fertility issues, head to RESOLVE: The National Infertility Association (they have a page in Spanish) for more information about infertility or to join a support group. Infertilidad Latina podcast is also a great resource for Latina women looking to learn and connect with others in their community.

Juliana Stoneback, who is half Colombian, is 2021 graduate of the University of Michigan. As the research project lead on MFA’s advocacy team, she has a particular interest in reproductive justice and health equity.

I am not your Sapphire

“I am not your Sapphire” Essay by LeAndrea Fisher, an infertility advocate and Detroit high school teacher of 25 years. She established Hope In Fertility, a ministry that serves to help the hurting and heal the broken. LeAndrea is also the founding Co-Chair of the Detroit, MI Walk of Hope; the first Michigan Walk of Hope partnership with RESOLVE: The National Infertility Association.

I am not your Sapphire. Not sure what I mean? Read on...

Historically, women of the African diaspora have been viewed through the lens of many stereotypes: the mammy, jezebel, Sapphire, and welfare queen. “The Sapphire portrayal has been around for as long as Black women have dared to critique their lives and treatments,” Dr. David Pilgrim, professor of sociology at Ferris State University explained in his 2008 article The Sapphire Caricature. Our feminine identity has been labeled as fiery, angry, loud, and mean.

These stereotypes become even more limiting and inaccurate when layered with a faulty reproductive identity. We have been associated with stereotypes of caring more for others’ children than our own, with sexual promiscuity and the propensity to reproduce more than the 2.5 children recognized as proper in the “ideal family.” The misrepresentation continues with labels including those who develop earlier, enter motherhood as teens who struggle to raise their children as lifelong recipients of welfare, who are both unmarried and uneducated. There are more stereotypes for Black women than I can adequately address here; however, I must speak to the limitations that have been superimposed on my sisters and dispel a few myths.

We are everything. This fact is a complete sentence. Among women of color, you’ll find those who are passionate and those who are meek and mild. You will also find those who observe all of the many nutrition plans, follow all forms of spirituality, and align with every thought and idea.

We are beautiful. Another fact. A simple observation of our many hues of melanin would lead anyone to the same conclusion. Beauty is sexy and I enjoy the sex appeal of my sisters for our own satisfaction; not for the male gaze or anyone else’s. Perhaps it's the sway of our hips or the rhythm in our stride or not. No one can pigeonhole us into one definition of Black womanhood.

We also embrace the joys and challenges that come with family. We decide how we define it and give it value. We decide to embrace singledom or become someone’s wifey. We set goals for what we’d like our family to look like and work to make that vision a reality. This includes being met with the same challenges one in eight couples face; infertility.

Women of color are more likely to face infertility and less likely to seek treatment according to the CARDIA Women’s study, “Racial Differences in Self-Reported Infertility and Risk Factors for Infertility in a Cohort of Black and White Women.” This is a contradiction to the stereotypes that many have embraced as fact. This can lead to a shame and embarrassment that can render us paralyzed. We find ourselves in disbelief when infertility is the diagnosis. Questions are avoided and specialty appointments go unmade. We just simply don’t know where to begin.

We avoid discussing our diagnosis or asking anyone for insight even though the statistics would suggest that infertility exists among us. I often remind my sisters that each of us can look around the holiday gathering and find a childless relative. We embrace them, love them, and fail to ask them to share their story. The shame allows them to hide in plain sight.

Many of my peers battle the expectations in our families, which only complicates matters. I was raised to avoid all sexual activity until marriage; finding my lifelong partner signaled that the time was right to grow my family. This is true for many women of color. Couples can often be forced to field questioning family members at the wedding reception of when babies will arrive. Others avoid the matter as they are expected to forgo motherhood altogether in the absence of a partner. As though the only acceptable invitation to the parent party comes through the hands of a spouse.

Navigating infertility is complicated by the poor medical care so many Black women receive. Too many of my sisters are rushed through annual exams in their 30s with no mention of reproductive options until they are told the window is just about closed. Others are offered a hysterectomy despite their desires limiting family building options significantly. Add in the complications of fibroids, endometriosis, and PCOS coupled with the distrust of medical professionals and bringing home a baby looks bleak. Very bleak.

But over the silent cries you can hear a sound. It’s the sound of my sisters calling out to each other; heart to heart. The same cry that longs for the family of our dreams, longs for a familiar face. Those who refuse to be denied break out of paralysis and defy the odds. We have the difficult conversations, get second opinions, hire fertility coaches, employ holistic medical practices, borrow and budget for fertility treatments, and find support groups. I did.

My infertility struggle led me to the Detroit Chapter of Fertility For Colored Girls, an amazing group of women bonded together by common experience. We are fiery as we toast to victories. We are angry with undesirable outcomes. Sometimes our tears of anguish are loud and navigating the medical system machine would make anyone mean. We are all of this and more.

The Sapphire stereotype of Black women is as ill-fitting as a dress two sizes too small; it’s simply inadequate for the task. All infertility warriors long for the day when the mysteries of infertility are solved and the legal, insurance-covered options all families deserve exists. While we wait, we gather freely offering support and strategy where our pain and beauty is no surprise.

Essay by LeAndrea Fisher, an infertility advocate and Detroit high school teacher of 25 years. She established Hope In Fertility, a ministry that serves to help the hurting and heal the broken. LeAndrea is also the founding Co-Chair of the Detroit, MI Walk of Hope; the first Michigan Walk of Hope partnership with RESOLVE: The National Infertility Association. LeAndrea serves on the MFA Advisory Committee.

Arab-American Academic: The Topic of Infertility is Taboo

Zena Hamdan is an Arab-American academic and public health administrator based in Dearborn, Michigan. She wrote her PhD on the perceptions of infertility in the Arab-American community in Dearborn and in that thesis she writes that for a culture so focused on family and home life, infertility “is considered a dishonor for any married couple.” Ms. Hamdan, who is the director of health education for the Dearborn non-profit C-ASIST and is on the adjunct faculty at both University of Detroit Mercy and Capella University, spoke with MFA’s Ginanne Brownell about infertility and the Arab-American community in Dearborn, Michigan. EXCERPTS:

Tell me a bit about your background?

I was born and raised in Kuwait. I'm originally Lebanese. So I spent most of my childhood in Kuwait. I moved to Lebanon in 1996 during my high school years and I did my first master’s there. I then got married and moved to the US in 2005. I got another master’s here in toxicology followed by a PhD in public health education and health promotion.

How did you decide to do your PhD on infertility in Dearborn’s Arab-American community?

I got really interested in the topic because I had a friend who had two kids at that time. She was really insisting to have the third but now she was around 40. When all this was happening, I was just starting my second year doing my doctorate. So I was not really sure what my research will be about. My friend at first tried naturally because that is how she had her first and the second kids. She tried for four years naturally, and then she tried IUI. And then IVF three times. And she was still insisting with no luck at all with the IVF. And I was wondering, “You already have two kids and they are grown up, now a pregnancy could be risky.” I’d like to know why, what was the actual reason behind it. So that got me thinking about the concept of infertility in the Arab-American population. The largest in all of the United States.

How did you start your research on this as it sounds like it could be a tricky subject?

I started looking up how Arabic-speaking individuals think about infertility. And I started realizing that it is one of the most sensitive topics that they don't like to talk about freely. A lot of their decision-making is basically impacted by their culture, their social beliefs, their values, religion, so a lot of health determinants are basically impacting their decision-making, especially when it comes to infertility. So my research question was, basically I would like to understand fertility perceptions among Arabic-speaking woman in Dearborn, especially those who are actually immigrants. Did those perceptions change over time? Did moving to a totally new geographic space change their way of thinking?

How did you do that research?

I had to do interviews with females seeking treatments so I was visiting private clinics in Dearborn. And try to basically get their approval if they would like to have me interview them regarding their infertility status. And it was so funny, some of the interviews, the husband would not allow his wife, to answer the questions by herself. He wanted to be there. And though it was about five years ago now, I didn’t forget one case where [the husband] was answering the questions instead of her.

So this is quite a taboo subject?

Correct, basically the topic of sex in general is taboo. It is the way they have been raised. It is something that is a shame to talk about. We don't teach [sex education] to our kids in schools [in many Arab countries]. So it starts from here, something that is hidden from the beginning. So when you talk about pregnancy, basically, it's through having intercourse, right? And if something has to do with infertility, and specifically, [it could] mean it has to do with something with an ability to do something, right? And it [can be something] related to males. That means he is not is not a man, right? That is [what many] believe. And for females, she's not complete if she cannot have kids. Motherhood is something that will complete the female. So this is how they look at it. That's why it is a very sensitive topic. Plus, basically for females, it's a topic of insecurity. It will put their marriage at risk. If a woman is infertile, that means it will open a door for their spouse to find another wife, because the purpose of marriage is to make a family and have kids.

But infertility, as we know, is nothing to be ashamed of. It’s a disease and something that one has no control over.

It is always how the community you're targeting perceives it. Do they perceive it as a disease? Do they perceive it as a curse? Or they perceive it as something that has no cure? Basically, some communities think that it is a punishment from God. You know, maybe the woman is not good enough. That's why God is punishing this woman by not actually allowing her to have kids. And with an infertility diagnosis, both men and women should [be checked]. But believe it or not, for this community, I'm specifically talking about the Arabic population, they will blame the woman first. Without even knowing the reason.

Is this the view of immigrant populations versus Arab-Americans born and raised in Dearborn?

Immigrants carry their beliefs, their values with them. And they will basically pass it to their kids and their grandkids. It is actually a very interesting question, an essential question that we can actually do research on to get these answers: are these new generations that are born here trying to change these perceptions or are they different in the way they're thinking right now? I don't have an answer.

So how does the community go about changing this view on infertility?

It something that is really complicated because it is not being addressed the right way. We are not bringing it up more, we're not talking more about it. Maybe if we actually raise the voice, talk louder about it in the community, maybe have discussion circles, seminars, workshops, it will be more heard. The community in Dearborn is actually growing bigger and bigger in size. We have refugees from Syria, Iraq, Yemen, so a lot of diverse populations coming in right now. And definitely they suffer from the same exact health disparities, that means we will be seeing inequalities and inequities receiving the health care that they need. We can do that through education and raising awareness, letting them know that it is okay to be infertile. Let them know that by seeking help, and the right health service, they could basically overcome this health issue. Not just stay quiet about it, this is not a solution. Encouragement from other people who are sharing the same health issue, talking about it more and feeling that you are not the only one in that boat. A lot of other people are in the same boat and they will actually be happy hearing about your story, because they have their own story as well.

A Community Suffering in Silence: Infertility and Arab-Americans

Layelle Beydoun was born and raised in the tightly knit Arab-American community in Dearborn, Michigan. (It is the largest of its kind in the United States with an estimated population of over 404,000). Soon after she and her husband were married, they discovered that conceiving wouldn’t come easy and that they would become infertility patients. The couple have been through countless surgeries and IVF cycles, so far to no avail. Through her rollercoaster fertility struggles, Mrs. Beydoun has become an advocate with RESOLVE: The National Infertility Association, participating not only in two national advocacy days and raising funds and awareness through Detroit’s Walk of Hope but also the recent Michigan Infertility Advocacy Day with MFA. She spoke with the MFA’s Ginanne Brownell and Nadia Shebli—who also comes from the same community— about her own struggles and why it is important that infertility be more openly discussed in the Arab-American community. EXCERPTS:

Brownell: Did you have any inkling that you would have infertility?

Beydoun: No. Growing up I had a very healthy lifestyle and had no major medical issues that would have indicated that I had an issue with my reproductive health. Still, I was diagnosed with having both a low anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) and a high follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), which meant I have diminished ovarian reserve (DOR) and I’m at a higher risk of premature ovarian failure (POF). When I asked why my biological clock was ticking much faster than normal, I was told, “You were just born with it.” There was nothing I could have done to prevent or cure this type of diagnosis which is chalked up to be unexplained infertility. Unfortunately, growing up I never had a pap smear or my blood drawn to test my fertility hormone levels and was actually discouraged from getting them since I was not sexually active. Had I been aware of my fertility health at an earlier age, I could have been proactive and used the opportunity to freeze my eggs while my hormone levels were still at an optimal number. This would have saved me so much time, money, and heartache but, fertility and infertility is not commonly discussed in the Arab American Community and in school our sex education classes teach us how not to get pregnant and fail to teach us how to get pregnant.

Brownell: Did you feel like you could tell anyone aside from your husband?

My husband and I are very fortunate to come from supportive and loving families. As soon as we heard about our infertility, we told our immediate family members so that they were aware of the struggle and challenge that we would have to go through to start a family. I didn’t start opening up about my infertility to others until almost three years after my diagnosis and treatments. The courage to talk about it came from infertility support groups outside my community and the national nonprofit organization group, RESOLVE. Although I’ve been an infertility patient for five years now, it still doesn’t stop other family members, friends, and acquaintances in the Arab-American community I live in from asking when I’m going to have kids if I have any yet, and what am I waiting for. When you live in a community that is not educated on the topic, their questions, concerns, and comments tend to be very insensitive even though that may not be the intention. It still discourages infertility patients, like me, from talking about our situation, which results in a community that suffers in silence.

Shebli: How do you think that connects to our community, this idea that no one discusses it?

Well, for as long as I can remember, no one that I knew in the Arab- American community talked about infertility and that’s because there’s a huge stigma surrounding the topic. I sometimes think that Arab Americans tend to feel a certain level of shame when they can’t conceive right away because our community still has an old-fashioned idea of how men, women, and couples should live their lives, and infertility goes against that image. Arab Americans have evolved in many ways but have not fully grasped the thought of how different and unique each family looks like nowadays. Whether it’s the blending of two families from a divorce, infertility, adoption, or interracial marriage, these examples are not usually expressed to be the normal idea of what an Arab-American family looks like even though it’s becoming more common.

Brownell: Why do you think that is?

The discussions we are having about infertility are very much outdated if we’re having them at all. Since infertility is such a taboo topic, our community has not had the opportunity to truly educate themselves on the actual issue. When infertility is brought up, too often I hear Arab- Americans more concerned with how it relates to their culture, religion, and reputation rather than it being an actual medical disease. With that being said, it’s hard to talk about something you feel you’re going to be prejudged about on something you have no control over. And how can we properly guide our future generations who may experience infertility with these uneducated ideas of what it is? Infertility is not a social status, it’s a disease.

Brownell: How do you go about changing the narrative?

Changing the infertility conversation. Having sex education classes also teaches how to start a family. Raising awareness in our community with the support of Arab-American medical professionals, political leaders, and educators. Forming a public infertility walk-in Dearborn where Arab- Americans come together to show their support and unity on the issue. Developing a support group that allows infertility patients to participate that makes them feel safe and also secures their privacy. Overall, just encourage the community to start talking about what obstacles infertility patients have to face in the state of Michigan to build their families.

Shebli: I grew up in a family of nurses yet I still feel like I don’t hear that much about infertility.

And that’s a part of a reason why I advocate and volunteer my hours in support groups and non-profit organizations: to raise awareness. I attend infertility support groups not only for myself but, to learn about other people's situations and further educate myself on the different experiences everyone has from a medical and social aspect. It’s important to continue the conversation because it may be a neglected topic now in our community but I want more for our future generations. Infertility might be an issue for my niece, or for my future daughter or son, or for my male and female cousins, friends or neighbors. I just don't want them to go through what I've gone through.

Shebli: Dearborn, of course, plays a huge role in the history of surrogacy, not just in Michigan but globally. Had you known that before?

No, and it was huge when I found that out during Michigan Infertility Advocacy day. It just blew my mind, especially because Michigan has had a bad grade for infertility. In 2020, Michigan was a grade D. This year it’s moved up to grade C. So it's definitely improving but, for the longest time, I think there was a lot of neglect when it came to talking about infertility in the state of Michigan.

An Inside Look at MIAD 2021

In the lead up to Michigan Infertility Advocacy Day (MIAD), Michigan Fertility Alliance (MFA) took on a number of current and recent University of Michigan graduates, all of whom are connected to the school’s Women’s and Gender Studies department. Their work has been integral and immeasurable in helping us make MIAD specifically and MFA in general a success in pushing to change the surrogacy laws in Michigan. Three members of our Advocacy Team were able to jump on calls we had with lawmakers and get a behind-the-scenes look at what a grassroots movement looks like. We asked them to write up their reflections of that day focused on the question ““What does advocacy look like to you after MIAD?”

In the lead up to Michigan Infertility Advocacy Day (MIAD), Michigan Fertility Alliance (MFA) took on a number of University of Michigan students and recent graduates, all of whom are connected to the school’s Women’s and Gender Studies department. Their work has been integral and immeasurable in helping us make MIAD specifically and MFA in general a success in pushing to change the surrogacy laws in Michigan. Three members of our Advocacy Team were able to jump on calls we had with lawmakers and get a behind-the-scenes look at what a grassroots movement looks like. We asked them to write up their reflections of that day focused on the question ““What does advocacy look like to you after MIAD?”

Seo Young Jang

Role at MFA: Legislative Project Lead

University of Michigan, Class of 2023

Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience

Gender and Health

As the Legislative Project lead on the Advocacy Team, my specific job was to work on setting up meetings with Michigan lawmakers and staff. Keeping neat spreadsheets proved to be vital for my job. I created spreadsheets for everything- from keeping track of every constituent’s individual representative and senator to notes on talking points. I was also responsible for setting up meetings, which became an intricate puzzle of scheduling for the big day of September 22nd. On the actual MIAD, I was busy fixing problems that arose the day of, including doing quick Google searches to figure out the world of Zoom to rescheduling no-shows. I had a chance to jump on a few of those calls as an observer, and it was so incredible and empowering to hear so many of these people I had been in touch with over the last few months sharing their stories with lawmakers.

Advocacy is a lot of logistics and setting up digital infrastructure, which can be frustrating and time consuming. But I also learned so much and am grateful for all the schedulers and policymakers who took the time to speak and email with me in the run up to MIAD. To me, advocacy looks like a lot of hard work but so very much worth the effort, as I think we all walked away inspired by what was discussed and what we are hoping to achieve. As a junior in college, I know that working with MFA to coordinate this historic MIAD is something that many my age cannot experience, so I’m extremely grateful to have had this opportunity.

Juliana Stoneback

Role at MFA: Research Project Lead

University of Michigan Class of 2021

Biopsychology, Cognition and Neuroscience BA

Gender and Health Studies minor

Seeing advocates empowered to share their stories on September 22nd was truly an incredible experience. MFA was able to organize meetings with 40 lawmakers and their constituents. The response from Michigan lawmakers and their staff emphasized how infertility impacts so many people as well as the importance of infertility awareness and advocacy. Infertility does not discriminate. People of all ethnicities, religions, ages, and socioeconomic statuses can struggle to build families of their own. In some cases, surrogacy is the only option for people to have children. I feel proud to be a part of such an amazing group of people in support of updating Michigan’s antiquated surrogacy laws and helping people build families. It was a great feeling to see all of our hard work pay off and the impact of MFA’s advocacy work. Thank you to everyone who shared their story and participated in MIAD.

Nadia Shebli

Role at MFA: Social Media & Engagement Lead

University of Michigan Class of 2022

Women's and Gender Studies, Biomolecular science

It was an honor to sit in on one of 40 meetings that were held on Michigan Infertility Advocacy Day (MIAD). I really valued being a part of such a historic day in the infertility community in Michigan. Given that this was the first MIAD, I was blown away at the number of advocates present to tell their stores as well as the lawmakers’ eagerness to hear them out and offer support. As a women's studies student and an aspiring physician, I find lived experiences to be invaluable indicators of where activism is necessary. I think that is what made this day so remarkable to me. The lived experiences of the constituents spoke volumes to the need for a change in surrogacy laws in the state of Michigan. I stood witness to a woman who was able to say her piece in the presence of a lawmaker who eagerly followed up with "What can I do to show my support?" In its purest form, I saw advocacy take place with the Michigan Fertility Alliance, which made me incredibly proud to be taken on as part of their advocacy team.

Periscope: Infertility & Race

According to the Centers for Disease Control’s 2002 National Survey of Family Growth, infertility is higher among married couples when the woman is non-white, with the incidence of infertility highest among Black women at 20%, followed by Hispanic women at 18% and then white women at 7%. Researchers found this was likely in part because of environmental factors, including living in more concentrated urban settings that can lead to more exposure to things like air pollution and toxic waste. But lifestyle aspects were also likely to play a part. Black women, for example, are more commonly affected by fibroids, which are non-cancerous tumors in or around the uterus that can be part of the reason a woman cannot have a baby. Obstruction of the fallopian tubes, also known as “tubal factor infertility”, is also more prevalent in Black and Hispanic women.

In September, African-American actress Gabrielle Union released her latest book, “You Got Something Stronger?” The autobiographical account focuses a chapter on her infertility and her surrogacy journey. Her story is not only important in terms of talking very openly about why couples (and some single people) turn to surrogacy, but also focusing on the importance of breaking the stereotype that infertility is only a white woman’s problem. Interestingly—and sadly—women of color experience medical infertility[1] at a higher rate than white women, with Black women twice as likely to experience infertility. Recent research published in the British medical journal The Lancet in April 2021, found that miscarriage rates are 43% higher in Black women.

According to the Centers for Disease Control’s 2002 National Survey of Family Growth, infertility is higher among married couples when the woman is non-white, with the incidence of infertility highest among Black women at 20%, followed by Hispanic women at 18% and then white women at 7%. Researchers found this was likely in part because of environmental factors, including living in more concentrated urban settings that can lead to more exposure to things like air pollution and toxic waste. But lifestyle aspects were also likely to play a part. Black women, for example, are more commonly affected by fibroids, which are non-cancerous tumors in or around the uterus that can be part of the reason a woman cannot have a baby. Obstruction of the fallopian tubes, also known as “tubal factor infertility”, is also more prevalent in Black and Hispanic women.

According to Judith Daar in her book “The New Eugenics: Selective Breeding in an Era of Reproductive Technologies”, over the years women from minority communities have often internalized their infertility, in part because their stories have been muzzled by social misconceptions about race, class, reproduction and fertility. For example, social and cultural factors may play a role in accessing fertility care in the Asian population and Asian-American women in general have lower pregnancy rates after IVF versus white women. Couples and women of East Asian descent often wait substantially longer before they consult a physician about fertility. Dr. Victor Fujimoto, the director of the IVF program at the University of California, San Francisco, told NBC News that they are much less likely to seek early intervention when they are having problems getting pregnant. “When we looked at our population of Asian patients,” he said, citing a report he co-authored in 2007, “40% or more were delayed in speaking for at least two years after their problem began.”

It is typically white professional-class women whose stories get told, with still almost no research on working class and poor women’s experiences with infertility. However, as Anna V. Bell writes in “Misconception” , slowly the myth of the “hyper-fertile [B]lack or [B]rown woman” has been transitioning from “a hushed reference” to being more openly acknowledged. That’s not only thanks to public figures from Michelle Obama to Angela Bassett, Naomi Campbell and Tyra Banks talking about their struggles with their infertility but also blogs like theBrokenBrownEgg.org and support organizations like Fertility for Colored Girls (FFCG).

Reverend Stacey Edwards-Dunn, the Chicago-based founder of FFCG who herself suffered from infertility, told me* that there are a lot of “myths and misconceptions of what it means to be a strong Black woman” and how that plays into fertility struggles. “We all grieve,” she said about infertility in general but, “there are some things attached to our grieving that other communities do not have to experience.” She went on to tell me that for many Black women that she counsels, it’s hard enough to have to explain to family and friends that they have to use a surrogate to have a baby. “What is more challenging is if you had to use a donor to get to that point as well,” she said. “I just spoke to a woman who is going to use a gestational carrier that I set up and that is her challenge. She was like, ‘it is one thing that I’m not going to be able to carry the baby, but how am I am going to explain that I had to use a donor?’”

Part of that might stem from the argument that perceptions around the inability to conceive are not just internalized, but also come from external forces too. There has been research that suggests that there is a lot of distrust in the U.S. healthcare system by men and women of color because, as Ms. Bell writes, of a “long history of racism and discrimination in the delivery of reproductive health care in general.” Some of that dates all the way back to the 19th century experiments by J. Marion Sims, who is considered to be both the “father of modern gynecology” and a controversial figure who operated on enslaved Black women both without anesthesia or their consent. “At the root of the gynecological practice, testing and research is the racist experimentation on Black women,” said Rev. Edwards-Dunn. “Dr. Sims embodied white supremacy and racism, which I think in turn is woven through medical education and people are very unconscious of that.”

There has been an inclination by doctors to diagnose white middle class women who are having trouble conceiving with having endometriosis, which can be treated by IVF. Black women, meanwhile, who are in the same situation are often diagnosed with having pelvic inflammatory disease, something often treated by a hysterectomy. As Ms. Bell has found, there are also lower referral rates of minority patients to infertility specialists though “[on] the other hand, physicians report that minority women, particularly African-American women” are much less likely to seek out treatment. That can then exacerbate any biological reasons. “Waiting to seek a diagnosis and treatment for infertility,” writes Ms. Daar, “means that the woman experiences reproductive aging in the interim.”

In the majority of films, books and television programs on infertility in general and surrogacy specifically, it’s often portrayed as being something that primarily affects white middle and upper-class women. So the image of “infertility as a white woman’s issue” has become normalized, writes Ms. Bell. Women of color who suffer from it are not seeing themselves onscreen, in books or the media so their feelings of alienation are reinforced because their stories are simply ignored or not depicted. Rev. Edwards- Dunn told me that when high profile Black women like Gabrielle Union speak about their infertility, it gets lots of media attention for a few weeks but then it drops off again. “There’s some surface conversation that is going on,” she said. “And we have to unwrap this onion and really get to the core of some of the issues, particularly that Black women and couples are dealing with as it pertains to issues of race and disparity around reproductive health and infertility.”

--Ginanne Brownell, MFA’s Media Liaison

*Some of this essay is excerpted from the upcoming book “How I Became Your Mother: My Global Surrogacy Journey.”

###

[1] Social infertility relates to lifestyle versus a medical situation. Social infertility affects gay and lesbian couples (who because of biology cannot reproduce together) or that of single men or women who are unable to find a partner to have children with. One definition states that it is, “an individual or couple, who during a 12-month period, possess the intent to conceive, but cannot due to social or physiological limitations.”

When Surrogacy is Your Only Hope to Become a Mother

MFA board member Alex Kamer was born with a congenital heart defect that prevented her from being able to carry a baby. Last year, her Indiana-based surrogate gave birth to their son. The MFA’s Parker Kehrig spoke with Alex about her experience as an intended parent in an out-of-state surrogacy.

Kehrig: How did you come to surrogacy?

Kamer: We [Alex and her husband] met with families who had gone both routes [adoption and surrogacy], just to try and learn as much as we could. We spent a year information gathering and having conversations with people. I don't think we ever really were like, ‘We feel 100% about one of these directions’, but we felt more driven, I think to try the surrogacy route to see if we could have a biological child. We wondered if we went the adoption route, if we would have regrets later on in life about not at least exploring the surrogacy option. I don't think that adoption is totally off the table, maybe we'll still do that someday.

MFA board member Alex Kamer was born with a congenital heart defect that prevented her from being able to carry a pregnancy. Last year, her Indiana-based surrogate gave birth to their son. MFA intern Parker Kehrig spoke with Ms. Kamer about her experience as an intended parent in an out-of-state surrogacy.

Kehrig: How did you come to surrogacy?

Kamer: We [Alex and her husband] met with families who had gone both routes [adoption and surrogacy], just to try and learn as much as we could. We spent a year information gathering and having conversations with people. I don't think we ever really were like, ‘We feel 100% about one of these directions’, but we felt more driven, I think to try the surrogacy route to see if we could have a biological child. We wondered if we went the adoption route, if we would have regrets later on in life about not at least exploring the surrogacy option. I don't think that adoption is totally off the table, maybe we'll still do that someday.

What was this journey like emotionally?

IVF was hard, it was a little extra complicated for me with my congenital heart defect, I needed to be followed a little more closely with all of the different hormones and drugs. And the toll that they took on my body, that part was rough. . You know, anytime you're out of the ordinary, you have to train people how to talk to you, and you have to do extra research, and you have to advocate for yourself.That can be really draining, but the emotional stuff didn't get didn't get weird until later on.

Could you tell me a little bit about that?

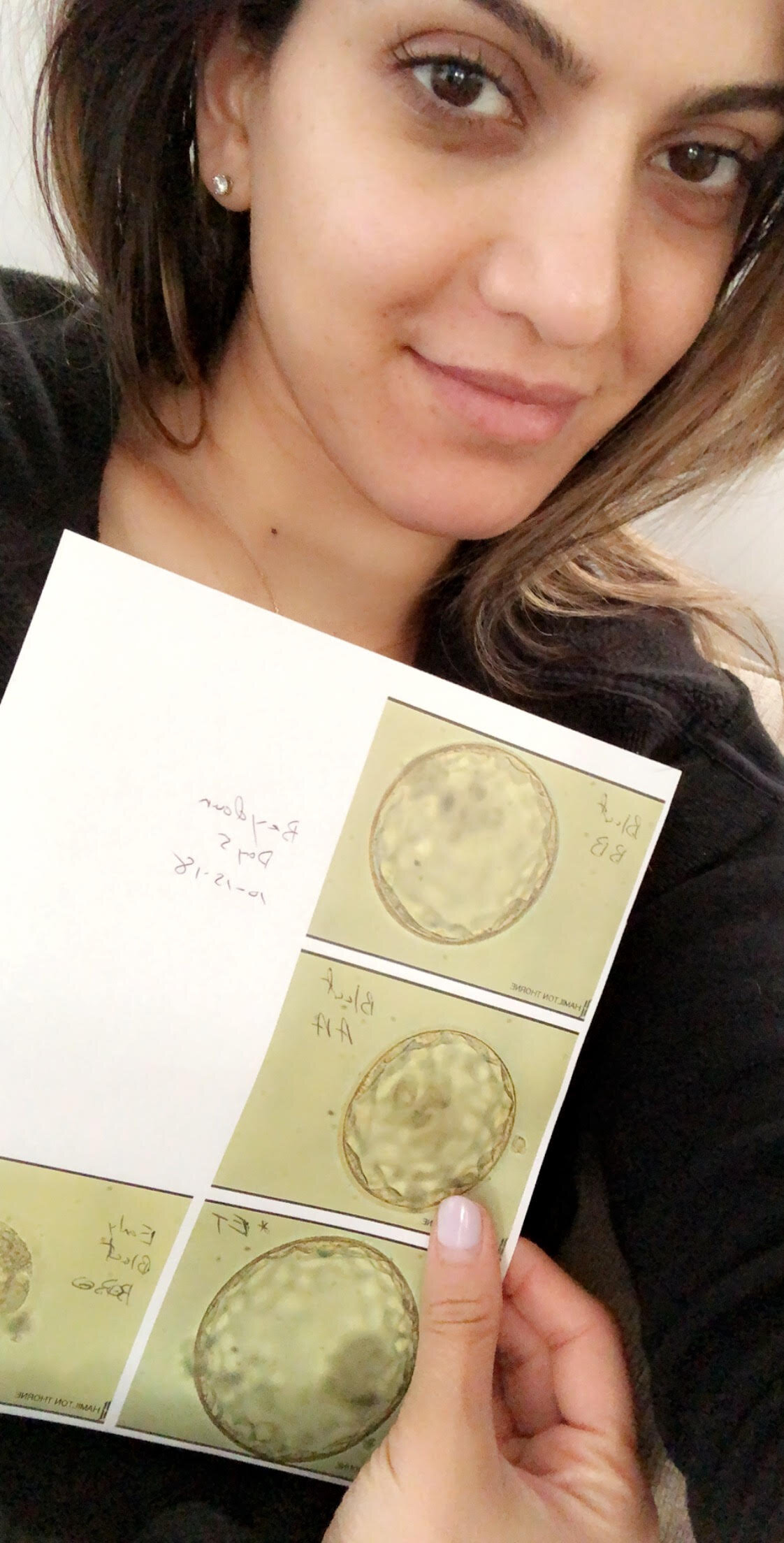

We had kind of an interesting journey. After IVF, we found an agency in Indiana to work with and had our embryos moved from Michigan to Indiana. We matched with our first surrogate, and we were so naive and excited when our first embryo transfer worked. She was super informed about pregnancy and took really amazing care of herself. And we had this great relationship, but she ended up having a miscarriage at about 13 weeks. We had been so optimistic, and felt like it was a sure thing because we had just gotten into the second trimester. And so that was awful. It was heartbreaking, she wasn't able to carry for us again. So we had to start all over. And then we found a new person, and she had a family emergency happen and wasn't able to continue. Then we had to start all over again and find a new surrogate.The first time we did an embryo transfer with her, she had an ectopic pregnancy. And then finally, our third embryo that we tried was successful and ended up with our son. During her pregnancy, of course, is when COVID started, so that added a whole other layer of anxiety.

That sounds incredibly stressful.

It's already a stressful situation when you're not physically with your baby, and you don't know what's going on. And you have to trust somebody, and it's just a hard relationship to begin with. Our reproductive endocrinologist who did the embryo transfers even said, ‘I've never had intended parents have so much trouble getting pregnant with a surrogate before.’ It took us a lot longer than it should have.

How did you cope with that?

After the miscarriage we grieved. We struggled, and we waited for a while before we started over again. We needed time to recover after that, because we were so all in on that pregnancy and so devastated to lose our baby. I think [my husband and I] became a little bit more guarded and cynical after that. And each embryo transfer, each step after that, we didn't believe it was real, until it actually came true. Our surrogate was about eight months pregnant with our son, and we were finally like, ‘we need to start believing that this is real and get a nursery ready because it's really going to happen’. It just felt like hurdle after hurdle and it wasn't ever really going to happen, and then finally did. We had to get over that cynicism.

What do you wish you had known when you started?

I feel like so much happened during our journey that doesn't happen for other people. I wish that I had known that it can be kind of a bumpy ride and there's a lot of hurdles to overcome, but that it's worth it. The relationship that you have with your surrogate is really important and the trust is important. It's hard to know what to anticipate when you have that initial match meeting, and you're just getting to know a potential surrogate, but really making sure that you ask all the difficult questions. Nobody could have expected a pandemic. The years of struggle, the financial and emotional burden - it was all worth it to build our family and to finally meet our sweet little boy last July.

Do you have any final thoughts?

The reason I'm doing this interview is because it doesn't have to be this hard, we shouldn’t have to go out of state. Maybe the law will have changed by the time we want to have a second child, but at the very least, we can make it easier for other people in the future. It's already a difficult process, the law shouldn't be a contributing factor. We should have support for men and women who are going through this process. And it should be a right, it should be an option for everyone who needs it.

A Gestational Carrier’s Personal Story

Nicole Cowles is a three-time gestational surrogate out of southern Indiana, carrying for a Michigan couple for the second time. She is a mother of three who also works at a hospital in Louisville, Kentucky. The MFA’s Parker Kehrig, interviewed Nicole about her experiences with out-of-state surrogacy.

Excerpts: Kehrig: What brought you to surrogacy initially?

Cowles: My mother was a women's health nurse practitioner. In my teens, she had taken care of a few women that had cervical adenocarcinoma. They had to have hysterectomies at a young age, and I felt so bad for them. I was only 16 at the time

Nicole Cowles is a three time gestational surrogate. Based in southern Indiana, she is carrying for a Michigan couple for the second time. Ms. Cowles is a mother of three who also works at a hospital in Louisville, Kentucky. MFA intern Parker Kehrig interviewed Ms. Cowles about her experiences with out-of-state surrogacy and why she became a surrogate. “To be so young, and hear some of those women having their fertility taken away from them was [heartbreaking,” she said. Excerpts:

Kehrig: What brought you to surrogacy initially?

Cowles: My mother was a women's health nurse practitioner. In my teens, she had taken care of a few women that had cervical adenocarcinoma. They had to have hysterectomies at a young age, and I felt so bad for them. I was only 16 at the time and I remember thinking, “Man, that's the only thing I want in life is to be a mom, I just want to be a mom.” I knew that once I finished having my own family, that was what I wanted to do. I wanted to carry for women that had the unfortunate circumstance of infertility. The first woman I carried for in 2016 is a cervical adenocarcinoma survivor. And then the second couple in Michigan, it was an issue where [the intended mother’s] lining would not build after numerous miscarriages.

How did you go about becoming a surrogate?

I had to submit an application, go through a psych evaluation, and then I was medically cleared by the clinic that the intended parents had used. It was a long process to get approved. They want to make sure of it you’re qualified and that you're going into this for the right reasons. You get matched with somebody who has like minded views, both matches I had were fantastic.

How were you matched with the intended parents?

The agency will ask questions like how many embryos you want to transfer per time, what are your beliefs on termination, what kind of couples would you want to carry for, etc. Since infertility brought me to surrogacy, that was who I wanted to carry for. And the agency had a match. In 2016. I carried for a couple in Chicago. And then 2018, I carried for a couple in Michigan. I am now pregnant with the sibling of the baby I carried in 2018.

What is it like carrying for a Michigan family, where surrogacy is considered a felony?

I couldn’t travel to Michigan for anything. Those couples spent $20,000 on making embryos, and they have to ship them out of state and hope they make it to their destination. That’s super scary, and it really just could have been avoided, had I been able to fly to Michigan and get pregnant up there. I’m currently pregnant, and I can't go up there and visit and do a fun ultrasound with them. I can't show their family, I can't be there for fun things like their son getting to touch my belly. It's only five hours away. But if I go up there and something happens. I'm technically a surrogate in Michigan. It's scary in that regard. My contract specifically says I am not allowed in the state of Michigan, the entire pregnancy.

What are your feelings about Michigan's opposition to compensated surrogacy?

Even with a flawless pregnancy, it’s still hard on you. Your body, you’re taking time away from your own children because of lifting restrictions, etc. You’re doing this to help somebody else who is in high need. Because of what surrogates go through, you deserve compensation, you are taking medication that has risks to have problems down the line. You’d never expect anybody like a teacher or a doctor, even if it's something they're good at, to go into something and not get compensated. My compensation, it paid for my college, it paid for my kids private preschool, it got me out of debt. I don't feel exploited.

You bring up exploitation, something that a lot of folks against surrogacy bring up. How do you respond to that?

With an agency and lawyers involved in a contract, exploitation is less likely. Because you have a contract drawn up prior to getting pregnant, it's very clear the way it's lined up. Prior to starting the medication, a large sum of the money had to be put into a third party escrow company that specialized in surrogacy agreements. This was to ensure things would be paid for and I would receive my compensation, it’s a measure that some states have made mandatory to reduce risk. I know personally of surrogates that have found ways to get compensated in Michigan and trust me, it is shady. People are going to do it regardless of the law. The best bet for state law is to get on board with everybody else, infertility isn't going away. Same sex marriage is legal and states that they have a right to grow their family. I feel like there's no logistical reason to criminalize people growing their family, we all grow our families in different ways. Adoption is not for everybody, there's not just babies everywhere to adopt. There are reasons people want to have a child of their own DNA, or a child from an egg donor, I just don't understand what benefit criminalizing [it] has.

What are the most memorable things about your experience as a surrogate?

When I gave birth both times, the intended parents were in the room. It was a remarkable experience to see the joy on their faces, all that pain and anguish that they had gone through was coming to an end to finally meet their baby. The financial reward was amazing. I was able to take my kids on some vacations I wouldn’t otherwise have been able to. There's a lot of good things. I have a good friendship with both couples. I’ve visited Michigan when not pregnant, to see the babies, and I'm Facebook friends with both the parents, it's really nice to see the updates. An added benefit that I don't think many know about is after you have the baby, you still make milk. I was able to be a compensated milk donor for premature infants. There's a high demand for that in NICUs right now, and it was amazing to know that it was the gift of surrogacy that would continue to be able to be given. It's changed my life. And I couldn't imagine not being able to be a surrogate.

The ACLU’s Challenge to Michigan’ 1988 Surrogate Parenting Act

In 1988, Michigan became the first state to criminalize surrogacy contracts. This law made participating in a compensated surrogacy contract a misdemeanor punishable by a fine of up to $10,000 and up to one year in prison. Meanwhile, arranging contracts became a felony with penalties of up to five years in prison and a $50,000 fine. Judge John H. Gillis Jr. of the Wayne County Circuit Court agreed to interpret the law to permit surrogacy contracts as long as the contract does not require the surrogate to give up her maternal rights to the child. In response, the Michigan branch of the ACLU filed a lawsuit challenging this Michigan statute on behalf of couples who participated in surrogacy arrangements as well as prospective surrogate carriers. Robert Sedler, Elizabeth Gleicher, and Paul Denenfeld were the attorneys who represented the plaintiffs in this case. In 1992 the Michigan Court of Appeals ruled that the law intended to criminalize surrogacy contracts for women to bear children for infertile people was constitutional. In an interview with MFA’s Ginanne Brownell and Juliana Stoneback, Ms.Gleicher, now a judge on the Michigan court of appeals, spoke about this case and why she felt it was crucial to fight this antiquated legislation.

In 1988, Michigan became the first state to criminalize surrogacy contracts. This law made participating in a compensated surrogacy contract a misdemeanor punishable by a fine of up to $10,000 and up to one year in prison. Meanwhile, arranging contracts became a felony with penalties of up to five years in prison and a $50,000 fine. Judge John H. Gillis Jr. of the Wayne County Circuit Court agreed to interpret the law to permit surrogacy contracts as long as the contract does not require the surrogate to give up her maternal rights to the child. In response, the Michigan branch of the ACLU filed a lawsuit challenging this Michigan statute on behalf of couples who participated in surrogacy arrangements as well as prospective surrogate carriers. Robert Sedler, Elizabeth Gleicher, and Paul Denenfeld were the attorneys who represented the plaintiffs in this case. In 1992 the Michigan Court of Appeals ruled that the law intended to criminalize surrogacy contracts for women to bear children for infertile people was constitutional. In an interview with Ginanne Brownell and Juliana Stoneback, Ms.Gleicher, now a judge on the Michigan Court of Appeals, spoke about this case and why she felt it was crucial to fight this antiquated legislation.

EXCERPTS:

Brownell: How did you come to work on this case?

Gleicher: At the time I was very active in the ACLU as a volunteer lawyer who handled primarily reproductive rights cases. In fact, I handled almost every reproductive rights case in Michigan for 10 to 15 years. I lost them all; we had a very conservative Supreme Court. When it came to reproductive rights, it was a natural fit [for them] to ask me if I would like to become involved. I saw [surrogacy] perhaps simplistically, and I still see it, perhaps simplistically, as just another facet of women and other people's, now men's, ability to make reproductive rights decisions on their own without governmental interference

Michigan, of course, has a very substantial history with surrogacy. Judge Marianne Battani was the first judge in the world, to rule that the intended parents, and not the surrogate, should be listed on the birth certificate.

It just shows you in some ways the power of judges. I know Marianne very well. And I don't remember the case you just mentioned, I mean, I sort of do, it's very, very fuzzy, but it doesn't surprise me that Marianne, a feminist, and a good judge would reach that decision.

So it sounds like you, Robert Sedler and Paul Denenfeld sort of knew this was not going to go your way but you went ahead anyway.

In many cases that the [Michigan] ACLU brings, whether they be in the reproductive rights arena or another one, the lawyers know that the chances of success are slim. But there are a few reasons that the cases have to be brought. Lawyers who volunteer for the ACLU try to vindicate the rights of people who have no other legal recourse, but an organization like the ACLU, or like a public interest law organization, somebody has to bring the fight to the courts for them, somebody has to speak for them legally. So that's what we wanted to do. I mean, now and I guess this is with the benefit of A) time B) age and C) being a judge, I understand that there's a historic component to what we do as well. I mean, we have to tell it, we have to make it clear for history that somebody stood up for that, that somebody protested, there was an active opposition to what was going on. There has to be evidence. That's what we created I think.

Has anyone been prosecuted under the 1988 law that you know of?

I've never heard of a prosecution. But I have heard of so many complications. For example, I wrote an opinion recently tangentially involving surrogacy. No one was prosecuted, in that case, but the complications that ensued from Michigan surrogacy law were substantial for that couple. The people who use surrogacy are usually educated, as I pointed out in my concurring opinion, financially able to use surrogacy, and they're not going to put themselves in line for prosecution. But that's not to say that there aren't serious consequences that befall people in Michigan trying to avoid the draconian effects of a stupid law. And we know it's stupid, because we're the only state that has it.

Tammy and Jordan Myers, a Grand Rapids couple, are in the process of adopting their biological twins because a judge ruled—against what Judge Battani ruled way back in 1986 but sticking to the 1992 Court of Appeals ruling—that legally they were the children of the gestational carrier.

Thinking about the Doe case, if it were presented today, to a Michigan Court of Appeals panel, would the result be the same? I'm not sure. There has been a change in the way judges think about these issues. I doubt that the court could leave its analysis with the baby selling rap, because we've seen that that hasn’t caused a revolution in baby selling and commodification of babies around the country. What has happened is that a lot of beautiful families have been created. And that's the evidence not, the wholesale destruction of the American family. I think that there would very possibly be a different result today.

Why didn’t you take the case any further, to the Michigan Supreme Court?

I think we didn't appeal because we knew we would lose. You know at that time, we had lost the reproductive rights cases. So we had a Supreme Court that was not very sympathetic to any of these issues. So why bother?

After Cancer, Becoming a Mother Through Surrogacy

After cancer, becoming a mother through surrogacy

Michigan resident Kim Samson (a pseudonym given to protect her identity) became a mother through surrogacy in 2020. MFA intern Parker Kehrig interviewed Ms. Samso about her experiences navigating this process. Excerpts:

Kehrig: Why is surrogacy important to you?

Samson: It’s currently and likely the only way that I'll be able to reproduce genetically with my spouse. So it's pretty important for us now, and sounds like it will be important in the future as well. We came to surrogacy when it became apparent to us because of a previous cancer diagnosis that I was not going to be able to carry a pregnancy. And we live in Michigan, so there was a lot to learn about how it was going to be possible to genetically reproduce. But we do have a baby now, so that's awesome. But it was definitely a struggle, and a lot of work.

Your friend was your surrogate. Tell me how that came to be.

At first we looked up agencies that recruit surrogates from out of state, because the state laws are so much better outside Michigan. It's very expensive, it wasn't something that we knew we could do. I got really desperate, I went to Facebook, which is not typically something I’d do with something so private. I wrote a relatively long post explaining the requirements in the state of Michigan and legally what the situation was, and that I couldn’t pay anybody for the service of carrying the child. My good friend from high school reached out to me and said, “Hey, you know, this is crazy. I was just about to be a gestational surrogate for my sister-in-law, who ended up getting pregnant on her own. I've been thinking about this and I was ready to do it. And then I saw your posts.”

So tell me about what the process was like.

We had already harvested my eggs and created embryos, so we had embryos created. In Michigan, both sides need to be independently represented by legal counsel. Our surrogate declined to be represented. My husband and I retained an assisted reproductive technology attorney. She draws up what's called a memorandum of understanding, not a contract, because in Michigan, surrogacy contracts are void and unenforceable. It preserves our original intent, it’s just something to have even though it wouldn't stand up in a court of law. Importantly, [our carrier’s] fertility clinic won't even consider going down the road of a gestational surrogacy without that memorandum and a letter of retainment from our attorney. Once the fertility clinic gets all of that documentation, we're also in Michigan required to go through counseling, then a report is created from those sessions, and that is also sent to the fertility doctor. They have to have all that paperwork in place before they can start with the medical process of getting a surrogate ready for transfer.

How did you navigate Michigan law through your surrogacy experience?

Nothing terrible, because we had a fantastic attorney. It’s expensive, and I know there's a lot of women who don't want to do that, and they want to try to work through the pre-birth order process on their own. And I'm a lawyer, and I know, I can't do that. It's such a strange legal process, because we're actually parties to a dispute, one of us as a plaintiff, one of us as a defendant, and a complaint gets filed. It's very strange.

What are the implications of being automatically labeled a plaintiff and a defendant?

In and of itself, it’s saying that there’s a dispute here over the physical and legal custody of the child, which there is not. My surrogate, from the very beginning, would get a lot of questions about how she was “going to give up the baby”, and she said she just looked at people and said, “It's not my baby. It never was my baby. It's [their] baby and I will be happy to hand her over to them when she’s born.”

Despite the laws here do you think there's anything that is like being done right in Michigan that should be preserved?

Certainly, the idea of someone carrying the child for you compassionately I don't think is a bad thing to do. I don't think that it needs to be looked at as a strictly commercial transaction. I think it's wonderful if someone wants to do this for you out of the goodness of their heart, and I would hope that that is the driving factor. In any case, I think doing it just for the money is probably not the right mindset. Or I would say personally, for me, it makes me feel good to know that someone did this because they are purely good. I know that's not the reality for everybody, if compensation makes the difference, and that's the way they can get to their children, then that's no judgment there either.

What about the ethical and moral debates around compensation?

The law seeks to align those two things quite closely. And whether you can be moral and still be compensated for carrying someone's child? Absolutely, I think so. I would have been happy to pay our surrogate a sum for this service. Pregnancy is a really big deal. She has two children of her own, she has a husband. And I don't think it's immoral. And I don't think it's wrong that she could have been paid a sum for the service of doing this for me and my husband.

Surrogacy in Michigan: Five Legal Cases You Should Know

For many couples who use surrogacy to expand their family, it can be a path fraught with emotional and financial hardship. And even once a child is born, many Michigan couples face another potentially grueling challenge: the battle for parental rights.

One of the most publicized legal battles related to surrogacy in Michigan occurred in the beginning days of 2021. After Tammy Myers of Grand Rapids was diagnosed with cancer and was told she had to undergo a partial hysterectomy, Ms. Myers chose to freeze her eggs so that she and her husband, Jordan, could still have children at a later date via surrogacy. The couple found a gestational surrogate, Lauren Vermilye, also from Grand Rapids, and their embryo transfer was successful. Ms. Vermilye carried and gave birth to the couple’s biological children, twins Ellison and Eames, on January 11, 2021.

However, the family were unable to leave the hospital together. Under Michigan state law, the couple weren’t recognized as the twins’ parents, because all surrogacy contracts are null and void in the eyes of the state. Instead, Ms. Vermilye and her husband were declared the twins’ legal parents, though neither have any biological relation to the children and filed multiple affidavits making that fact clear.

Michigan state courts, however, tend to follow the Roman law principle mater semper certa est (“the mother is always certain”), which grants parental rights to the woman who carried the children, regardless of biological connection. This left Tammy and Jordan with only one option: to undergo the lengthy and complex process of adopting their own biological children. (It is important to note that this is standard practice for most European countries, including the U.K. where parents of children born through surrogacy must obtain a parental order because “If you use a surrogate, they will be the child’s legal parent at birth.”)

The Myers case echoes other historic cases in the state over the decades.

Back in 1988, a Michigan court ruled, like in the Myers’ case, that Laurie Yates—who was a traditional surrogate meaning she was also the egg donor— and her husband of Ithaca, Michigan, were the legal parents of the twins that she had carried for Jonesboro, Arkansas couple Barry and Glinda Huber. Before the twins’ birth, all parties had agreed that the Hubers were the intended parents through a legal contract written by Dearborn, Michigan lawyer Noel Keane.

A legal battle for permanent custody ensued, but in the meantime, the newborn twins—Stephanie and Anthony—were transferred between the Hubers’ and the Yates’ care every two weeks. This type of upheaval, especially at such a formative time in the babies’ lives, causes immeasurable emotional turmoil and anxiety for all parties.

The all-too-common theme of battling for parental rights and child custody has repeated itself in the case of another Grand Rapids couple Amy and Scott Kehoe. Due to their struggle with infertility, the Kehoes used an egg donor, sperm donor and a surrogate to carry their twins, Ethan and Bridget. While the Kehoes were able to take their children home from the University Hospital in Ann Arbor after their birth in 2009, they were ordered by police to relinquish their custody a month later.

The Kehoe's surrogate, Laschell Baker of Ypsilanti, filed a court order to obtain custody of the twins after she learned that Ms. Kehoe was being treated for mental illness. Because Michigan law did not uphold the surrogacy contract between the Kehoes and Ms. Baker, regardless of their agreement on child custody, all parties were forced to battle the case in court. Ms. Baker won custody of the twins.

Michigan surrogacy law made a name for itself in another recent highly publicized case. In 2012, a Connecticut couple struggling with infertility worked with Crystal Kelley, also from Connecticut, as their gestational surrogate. The amicable relationship between the couple and Ms. Kelley grew tense when 21 weeks into the pregnancy an ultrasound revealed severe congenital defects. While the contract between Ms. Kelley and the intended parents clarified that she would have an abortion in the case of severe fetus abnormality, Ms. Kelley ultimately refused to terminate the pregnancy.

Because Connecticut law recognizes the biological parents as the legal parents in surrogacy cases, the couple indicated they planned to obtain custody of their daughter and surrender her to the state under Connecticut’s Safe Havens Act for Newborns. Faced with this possibility, Ms. Kelley chose to flee to Ann Arbor, Michigan, where she knew she would be granted parental rights as the gestational carrier of the child. After her birth, the baby, Serraphina, was adopted by Rene Herrell. Sadly, she died in 2020 at the age of eight due to complications from a necessary heart surgery and an ensuing infection.

Intriguingly, in 2018 a Michigan judge used the 1988 Surrogate Parenting Act to determine a ruling in a custody battle between lesbian parents. Back in 2011, Michigan residents LaNesha Matthews and Kyresha LeFever became a couple and decided they wanted to have children. Ms. LeFever underwent an egg retrieval, those eggs were then fertilized with sperm from a donor and transferred to Ms. Matthews’ uterus. Soon the couple found they were pregnant with twins.

When the babies were born, Ms. Matthews was listed on the birth certificate while Ms. LeFever was not, but the children had LeFever as their surname. The couple raised the twins for a few years together but in 2014 they split but decided to co-parent. However in 2016, Ms. Matthews developed serious health issues so Ms. LeFever took over as the primary parent.

Unable to sort out a custody agreement between themselves, Ms. LeFever filed suit in 2018, where the judge ruled that Ms. Matthews—who gave birth to the twins—was not a parent to the children but simply the surrogate. (Ellen Trachman, who wrote about the case in Above the Law state that, “As an attorney that practices in and writes about surrogacy on a daily basis, I can assure you that LeFever and Matthews’ birth and parenting arrangement was in no way a form of surrogacy.”)

in April 2021, the Michigan Court of Appeals unanimously reversed the lower court’s decision and found that the court was incorrect to use the determination that Ms. Matthews was a surrogate under the 1988 law. Judge Elizabeth Gleicher and her colleagues on the court also found error in the previous ruling that the term “natural parent” was limited just to those genetically related to a child.

—Ginanne Brownell (MFA media consultant) and Claire Bletsas (former MFA intern)

An Interview with Stephanie Jones

Stephanie Jones, Founder, MFA

Stephanie Jones is the founder of the Michigan Fertility Alliance (MFA). She is the mother of two children, one of whom was born via a gestational carrier in Kentucky in June 2020. The MFA’s Advocacy Team Oral Historian, Parker Kehrig, interviewed her about the reasons she is fighting to change the surrogacy laws in Michigan. Excerpts:

Kehrig: Why did you start the Michigan Fertility Alliance?